The Adoptee Rights Organization

Bastard Nation History, Analysis, and Endorsement

of Citizenship, Deportation

and

The Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2019-2020

September 9, 2020

(Revised and updated from 2015 document)

This report will be updated when appropriate.

A shorter bullet point version of this report is here

Until 2000 children adopted internationally by US citizens were required to undergo a naturalization process prescribed by US law. Depending on the type of visa the child traveled under to enter the US, some were granted automatic citizenship while others gained citizenship only after their adoptive parents “re-adopted” them in the US following procedures outlined by federal and individual state law.

Unfortunately, many adoptive parents did not research or verify citizenship status at the time of adoption or follow through on the citizenship process. Some say they were unaware of naturalization requirements and believed citizenship was automatic upon adoption finalization. Some claim to have been misled about citizenship procedures by their adoption agencies, courts, lawyers, or federal immigration authorities. Some believed that it was up to the adoptee, at the age of majority, to choose their citizenship status. In some cases adoptive parents disrupted the adoption, and either “rehomed” the children they brought to the US or turned them over to the state foster care system where they lingered with no legal closure.

Decades later these misunderstandings and failures led to legal problems—including deportation proceedings– for international adoptees years after their adoptions were assumed “finalized” and citizenship granted. Most of these adoptees had no idea that they were not US citizens until they attempted something as simple as registering to vote or were convicted of minor crimes—even misdemeanors—and fell under the gaze of government authorities.

The passage of the federal Child Citizenship Act of 2000 (text) (CCA) attempted to remedy this situation by granting automatic citizenship to those born on or after February 27, 1983, the effective date of the legislation.

Those adopted before that date were left behind, subject to federal investigation and possible deportation under the old system. The situation became worse after 9/11 when legal identity and proof of citizenship came under critical scrutiny by federal, state, and local governments. Since then, the number of international adoptees deported or in the deportation pipeline has grown dramatically Most, before and after 2000 have been convicted of minor non-violent offenses particularly controlled substance possession; others reportedly investigated and threatened with deportation for simply applying for a Pell Grant or Social Security benefits. One absurd pre-2000 case involved German adoptee, Mary Anne Gehris, an administrative assistant and mother of two in Covington, Georgia, who in 1998 applied for citizenship so she could vote and accept scholarship money. She admitted on her application that ten years earlier she had been convicted of misdemeanor battery for pulling a woman’s hair during a “spat” over a boyfriend, and had done a year’s probation, and community service. She avoided deportation when the Georgia Board of Pardons and Parole granted her a pardon to keep her in the US. She became a US citizen in 2001. Under today’s Draconian legal procedures she would likely be deported.

The federal government keeps no statistics on the number of adoptees who have been deported or how many adoptees are in the US without US citizenship. We are therefore forced to rely on media reports on individual deportation cases or activist-researchers also hampered by poor official statistic keeping. The most complete documentation is located on the website of the adoption watchdog Pound Pup Legacy. Other stories are collected on adoptee citizenship activist web pages run by the Adoptee Rights Campaign and Adoptees for Justice. A general article on Korean adoptee deportation can be found on Wiki. Some researchers believe that the number of “illegal adoptees” in the US is about 15,000. but the number could go as high as 35,000. according to activists. Many probably are not aware of their “illegal” status and some may not even know that they are adopted. To make matters worse, those who learn they aren’t citizens are fearful of coming forward to apply for citizenship because under the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1996 they can be charged as undocumented by INS/ICE and subject to deportation. The law gives judges little discretion to stay deportations.

Currently, America’s “illegal adoptees” cannot gain permanent resident status. They cannot legally hold jobs or driver licenses or register vehicles, open bank accounts, join the military, receive security clearances, apply for US passports, or receive any number of government entitlements or funds—including Social Security that they or their spouses have contributed to and are eligible to collect.

Adoptee deportees have little or no memory of their countries of origin. They have no native-language skills and no family, friends, or support system in their first countries. Most have no means of employment in their original countries due not only to those limitations but because those governments severed citizenship when the child was adopted to the US. News reports indicate that deported adoptees often end up in homeless shelters and the streets—or worse– when returned to their countries of origin.

Who is Deported

What we do know is that the majority of adoptee deportees are Asian and Latinix, most adopted as infants or toddlers by white parents, some military. Some deportees, such as Rudi Richardson/Udo Ackerman, and Monte Haines/Ho-Kyu Han<(Korea),in fact, are veterans whose status wasn’t flagged when they enlisted in the military. A number of deportees such as Adam Crasper (Korea) and Jennifer Edgell Haynes (India) are victims of child physical and sexual abuse, disrupted adoptions, and abusive foster care.

- Joao Herbert was adopted from Brazil at the age of 8 and deported after a misdemeanor marijuana charge for which he performed community service. Two years later he was murdered in the poor suburb in which he lived. He taught English in a school outside of Rio, where he was known as “the American professor.” He was married, and had a child. News reports indicate that he had become involved in a drug operation to secure funds to return to the US. clandestinely.

-

Jennifer Edgell. Deported to India. Adopted without parents’ consent. Sexually abused by two adoptive families. Shipped to nearly 50 foster homes. Jennifer Edgell Haynes born in Mumbai, India in 1981, was left in the custodial care of an orphanage when she was 5 years old. At the age of 8 she was adopted, without the consent of either parent, by an American couple. Her new father sexually abused her, and she was removed from the family and placed in a second family, where she was again sexually abused. In less than a 10-year period, Jennifer was passed around to nearly 50 foster homes. Neither adoptive families nor her now-defunct adoption agency, completed her citizenship process She was deported to India in 2008 after serving time for drug possession. She is married to an American citizen and left two children behind in the US. Her case has wended its way through Indian courts. Due to her unresolved citizenship status in India, Jennifer lived in shelters for several years and was finally granted Indian citizenship. Indian journalist Nadita Puri published Jennifer’s story in her latest book, Jennifer, One Woman, Two Continents, and a Truth Called Child Trafficking.

- Alejandro Ebron was deported to Japan after a series of drug possession convictions and a shoplifting charge. He was adopted in 1959 at the age of 1 by a US sailor stationed in Yokohama and his Filipino wife. Two years later the US Immigration and Naturalization Service canceled Alejandro’s citizenship hearing because his adoptive father was at sea with the US Navy and unavailable to attend. Ebron’s adoptive father was in Vietnam until around 1970, and his seriously ill adoptive mother didn’t continue the citizenship process. Ebron says he always believed that he was half Mexican and half Filipino. He assumed he would be deported to Mexico. He was stunned when he was sent to Japan.

-

Jess Mustanich, deported to El Salvador. Adoption agency went out of business and US authorities stonewalled naturalization for years. Nearly 15 years ago, Jess Mustanich was deported to his native but unknown El Salvador after he was convicted of burglary when he and some friends broke into his adoptive father’s home. In 2005 Jess’s adoptive father, Bill Mustanich, told the San Diego Union Times that he and his lawyer ran into problems 15 years earlier when Jess was 5 and he tried to re-adopt him under the then-law. (The Mustanichs had just concluded a protracted divorce and custody battle and Bill had been granted full custody of Jess while his ex-wife got custody of two adopted girls.) The unnamed agency that helped handle the adoption closed and laws changed. The elder Mustanich says he was stonewalled by Immigration & Naturalization as well. An INS clerk refused to accept the required re-adoption application and gave him an INS phone number to call instead. Bill said he left several messages but never received a response. As Jess grew older he began to exhibit psychological problems and ended up in residential treatment and state care since according to the law, Bill Mustanich, though he had repeatedly requested court help with the adoption procedure, had no legal authority over Jess. Upon release from San Quentin in 2003 on the burglary charge Jess was transferred to an ICE detention center where he was stripped of his American and Mustanich identity and referred to as Alfaro, the last name of the birth mother he never knew. Bill Mustanich says, “I think what the government has tried to do is strip him of his American Anglo identity, I think they have taken Mustanich away because they don’t want a Mustanich being deported to El Salvador. What a horrible thing it would look like if he turned up dead.” Jess was deported in 2008. Last reports , which are several years old, indicate he was learning Spanish, receiving financial assistance from Bill and from Salvadorian Seventh Day Adventists.

-

Anissa Druesedow de Thelwel, deported to Jamaica.; now lives in Panama. Adopted by US military family. Teenage cancer survivor Adoptive parents considered her a “walking medical bill” and refused to help her because “she broke the law.” Anissa Druesedow de Thelwel was born in Jamaica in 1970, When she was 6 her biological mother took her and her sister to Panama to live where she was sexually abused by her mother’s boyfriends and family members. Later when her mother abandoned the siblings to their grandfather, he put them in an orphanage where the abuse continued. In 1982 Anissa and her sister were adopted by an American couple stationed at the military base in Panama City. Six years later, back in the States, she was diagnosed with cancer and her left leg was amputated. When she turned 18 military insurance expired. She became, she says, “a walking medical bill” and her adoptive parents let her know she’d out-stayed her welcome. By 2003, Anissa was a single mother holding down dead-end jobs and with an ex-husband who refused to pay child support. She was convicted of Grand Theft (no details) and sentenced to at least one year in prison. During prison processing ICE informed her she had not been naturalized; therefore, not a US citizen. Federal authorities put a hold on her keeping her from participating in the work-release program or resuming her old job which her former employer had promised her. Her adoptive parents said she’d broken the law and refused to help. In 2006 Anissa was deported to Jamaica where authorities, although the government had accepted her, did not believe she was Jamaican and didn’t want her. She made her way to Panama where she has re-married and now lives. Anissa volunteers at local orphanages, including the one she lived in as a child, works as a translator, and is active in internet adoption forums and the ACA campaign. She hopes to be allowed to return to the US.

Susan Hill, (and here) ) now going by her original name Viviana Isobel Diaz-Henao, is one of a sibling group of five adopted from Medellin, Columbia in 1989 by a couple in Virginia who had already adopted 9 children internationally. She was 6 years old. Susan had a problematic relationship with her new family, ran away eventually, and stayed with family friends, and in group homes. As a teenager, she served time on a drug charge and was convicted of small non-violent crimes. When she was caught driving without a license, she signed her sister’s name to the ticket, which triggered an investigation, and landed her in the deportation tank for forgery. Susan was legally adopted, but unlike her siblings, she was never naturalized. Her adoptive parents now say they were “too busy” with 14 children to complete the process. Her siblings believe the adopters just wanted to get rid of her. She was deported in 2012 and in 2015 lived in Medellin where she located her birthmother and taught English. In late 2015 Susan, in an attempt to reunite with her 7-year old son she hadn’t seen since he was 3 months old, was apprehended at the border when she attempted to enter the country. ICE agreed to reopen her case. We are unable to find an update on her status. Last we heard, she was being held at a federal prison in Houston Texas, and working with Nexus Services to regain legal status. According to news reports, at that time she was in the process of applying for two separate visas for victims of human trafficking and abuse.

Ella Purkis, adopted from Korea in 1956 at the age of 2, is an electrician with security clearances to work on military bases and in nuclear plants. In 2012 her husband became seriously ill, and she was forced to stop working to care for him. After his death, she attempted to file for her husband’s Social Security Survivor’s Benefit. Ella was informed that she was not a US citizen and advised to apply for a US Certificate of Citizenship. Her request was rejected because she was over the age of 18 and told that her adoptive parents couldn’t “transfer their citizenship” to her. Due to a US Senator’s intervention, Ella received a temporary Green Card which enabled her to collect benefits. On July 8, 2016, she was granted US citizenship.

-

Rebecca Wilson Trimble. Deportation to Mexico pending. Came to US at age 3 days. Charged with entering country without a visa. Parents waved across the border with no document check. Passage of ACA won’t help her. Rebecca Wilson Trimble, 30, was born to a 12-old girl in Baja California, Mexico. Her adoption, at the age of 3 days of age, was arranged by a friend of the Wilsons living in Mexico and the doctor who delivered her. After receiving a Mexican birth certificate listing her adoptive parents as her legal parents which was the only document they were told was required–they returned to the US where they were waved through the border crossing, the routine practice of the time. The Wilsons say they were unaware that they needed to gain custody through a Mexican court order and then apply for the appropriate visa for the baby at the US Consulate. They believed that the birth certificate served as proof of citizenship. In 2012 Rebecca ran “afoul” of the law when just before her marriage, she applied for an enhanced ID to ease a honeymoon road trip through Canada. and was informed that she needed better proof of citizenship. Her case has dragged through the bureaucracy since then. In 2016, her husband, John Trimble, in the military at the time, filed for a Green Card spousal exemption, to accelerate her application and permit her to stay in the country. The application was denied with the government saying she had entered the country lawfully and should go ahead and apply through regular channels for the Green Card. Later, authorities turned around and decided she was here illegally, and even worse: she had voted illegally in the 2008 federal election. In the meantime, the Mexican government questioned the authenticity of the Mexican birth certificate given to her adoptive parents. Although she was born in Baja , the certificate was issued in Oaxaca 2000 miles away, and there is no record on file of the Mexican birth certificate issued to her adoptive parents, though they possess hospital records. Rebecca currently lives in Bethel, Alaska where her husband is the town’s only dentist. Her lawyer recently filed suit against INS, and both Alaska senators have filed private bills to grant her citizenship. Unfortunately, if federal legislation is passed (see below) to cover nearly all those already deported or in the pipeline, it will not cover her, because she had no visa at the time she entered, the US. The New York Times has covered her ordeal in detail.

At least one documented US-born adoptee has been deported.

-

Mark Lyttle, born and adopted in the US, deported to Mexico (later Guatemala, Honduras and maybe Nicaragua). despite FBI report and other documentation that he is US citizen. He “looked Mexican.” North Carolina-born and adopted Mark Lyttle, (here, here, here) was shipped off to Mexico after serving time for assault. Lyttle has a history of mental illness. He attested alienage (but also made contradictory statements) to ICE which took his word over FBI records that indicated US birth and citizenship. Besides, he “looked Mexican.” (Lyttle’s biological father is part Puerto Rican.) Lyttle returned to the US after Mexico deported him to Honduras., Honduras, in turn, sent him to Guatemala (and perhaps Nicaragua) where he was able to connect with the US Counsel who cleared the way for him to return to the US in a matter of hours. Upon arrival, however, ICE attempted to deport him again, but finally OK’d his release after pressure from his lawyer. Lyttle successfully sued ICE, which admitted no wrongdoing and was awarded an unspecified settlement.

The US isn’t the only country deporting adoptees

The United States is not alone in de-citizening its international adoptees. In 2016, the Australian Department of Immigration and Border Protection, reportedly to prevent trafficking, said that amended Australian birth certificates, issued as part of the adoption process, are no longer lawful evidence of citizenship leaving the citizenship of thousands of internationally adopted Australians –including those who hold Australian passports–in limbo. At best they are forced to apply for the citizenship they believe they already hold. This year, Stephanie Mathews, 24, adopted at the age of 4 months by Australian nationals working n British Columbia, was denied citizenship and permission to live in Australia with her now- retired parents. Her request for an adoption visa was also denied because the state refuses to accept the legality of the adoption since it was private.

Litigation

International adoptees in and out of the deportation pipeline and their families have sought localized legal redress with various outcomes.

Deported adoptee Adam Crapser, (and here), however, has taken his claim a step further by filing a civil action for 200 million won ($177,000 in damages against the South Korean government and Holt Children’s Services based in Seoul, the agency that handled his adoption. He charges gross negligence regarding his adoption and by extension the adoption of thousands of other children shipped overseas. Crasper argues (and he is not alone) that the Korean government, more interested in economic growth than the welfare of so-called orphans was willing to export thousands of “orphans” via profit-driven adoption agencies supported by foreign adopter fees with little regard to fraudulent paperwork and citizenship issues that could develop later. Authorities, in fact, knew the identities of many of the “orphans” who were adopted overseas. Other children were simply lost and swept into orphanages. Until 2013 international adoptions, in fact, were not even required to be heard in local courts.

Crasper’s, case history which includes foster care, two adoptions, and physical and sexual abuse exemplifies the brokenness of international adoption and the dire need to amend the ACA.

In 1973, when he was 3 years old ,Crasper and his biological sister were placed by Holt with an abusive couple in Michigan. Seven years later they abandoned the children. He was separated from his sister and shuttled to numerous foster and group homes. At the age of 13, he was placed with a second couple, Thomas and Dolly Crasper, in Washington State, who continued the abuse which included banging their adopted children’s heads against walls, striking them with kitchen utensils, and burning them with heated objects. In 1991 the Craspers were arrested and charged with physical child abuse, sexual abuse, and rape. They were eventually convicted of criminal mistreatment and assault. Later, Crasper himself was convicted of burglary after he broke into their home to retrieve a stuffed dog, rubber shoes, and a Korean-language Bible, the only remnants of is pre-adoptive orphanage life in Korea. He has other convictions for possession of a firearm and assault of a roommate. Not surprisingly, neither set of adoptive parents bothered to file for citizenship.

In 2014, Crasper, who by then had straightened out his life, married, had 3 children and had worked as an insurance adjuster and small business owner, applied to renew his Green Card. Instead of renewal as he expected, he was greeted with his youthful rap sheet ,,an immigration investigation, and thrown into an ”immigration detention center “in Tacoma, Washington for 9 months His request for a discretionary “cancel of removal order” which would have permitted him to stay in the US was rejected. Desperate to get out of jail he refused to appeal the ruling and was deported in November 2016. In Korea, Crasper has met his birthmother. She says she was single, desperately poor, and disabled when she left her children at the orphanage. Now she feels she “horribly sinned” against her son.

Crasper’s case wends through the Korean courts and may take years to settle. Holt shrugs off the allegations saying it did everything it had to under Korean law at the time and blames adoptive parents in general for not following through on naturalization, even if they many say they were never informed they needed to pursue the procedure. They also blame Korean Children’s Services for adoption foul-ups. He says he’s not interested in the money but wants to Korean government to acknowledge its responsibility.

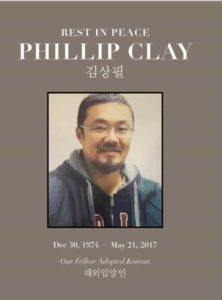

NOTE: On May 8, 2017 another Holt-handled deportee, Phillip Clay, (and here) committed suicide by jumping from a 14th story apartment building in Ilan. Clay had a long history of legal, drug, and mental health issues and friends in Korea say he had difficulty coping with deportation, cultural, and language problems. Korean adoptee expats claimed that Holt, Children’s Services, resisted holding his funeral and was convinced only by pressure from Korean Children’s Services , which co-hosted. Moreover, the agency refused to hold the service in English, the common language of the Korean adoptee community. Later Korean Children’s Services provided a translator. Funeral attendees also claimed that Holt chairwoman Molly Holt smeared Clay at the funeral, complaining that he had recently come to her office in a taxi paid for by Holt, and “used all their ink and paper.” Holt also claimed that it had never been Clay’s legal guardian, only that it had facilitated his adoption.

US Legislation

Since the passage of CCA 2000 three attempts have been made to close the pre-2000 “loophole,” but have met with resistance even by members of Congress who “get it.” A major stumbling block has been a concern over a “pathway to citizenship” for those convicted of crimes and deported to their country of origin. The bills are a hard-sell with adoptee citizenship being conflated with immigration controversies. Reportedly. some conservative legislators who actually supported earlier attempts to amend the ACA are hesitant to step forward for fear of being perceived as ‘pro-immigration.”An amended, inclusive ACA they say, can be the camel’s nose under the tent regarding immigration loopholes even though international adoption is not an immigration issue and is, in fact, deeply promoted by US foreign policy. In general, then, international adoption has been caught in the crosshairs of current and proposed immigration policy and controversy now more than ever under the Trump -Stephen Miller regime.

- In 2015 US. Sens. Amy Klobuchar, (D-Minnesota), and Jeff Merkley, (D-Oregon) introduced S2275, The Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2015/2016 (ACA) an amendment to the Child Citizenship Act of 2000. Rep. Adam Smith (D-Washington) introduced HB 5454, the companion bill in the House. The bill retroactively granted citizenship to nearly all adoptees who did not fall under the original CCA law. Exceptions were made for those whose criminal charges had not been resolved. The bills had little support and died in committee without hearings.

- HR.5233/S.2522: The Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2018 was a rehash of the 2015/16 bills. Passage would have granted citizenship for international adoptees born prior to February 27, 1983, except those deported due to conviction of crimes of physical force against another person. They, too, died in committee without hearings

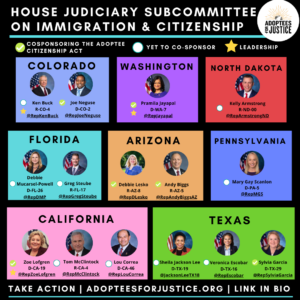

- Currently,H.R. 2731/S.1554. (ACA 2019-2020) are running in both houses. Introduced in May 2019, the proposals enjoy non-partisan support. They cover international adoptees who lawfully entered the US, but did not meet the age restriction of the current law. They apply to nearly all those who have been deported or are residing in another country on the effective date of the bills, and whose criminal cases have been resolved pursuant to appropriate legal authorities. The House version is in the Subcommittee on Immigration and Border Security. The Senate version is in the Judiciary Committee. No hearings are scheduled, but support has picked up over the years. As of this writing, the House bill sponsored by Rep. Adam Smith (D-WA) has 61 co-sponsors; the companion Senate bill, sponsored by Sen. Roy Blunt (R-MO), and has 8 co-sponsors.

Bastard Nation Believes

Bastard Nation supports the Adoptee Citizenship Act 2019/2020, the amendment to the Child Citizenship Act of 2000. We believe:

- All adoptees, adopted domestically and internationally, should be treated equal and fair under law.

- All individuals adopted by US citizens should enjoy the same citizenship rights and responsibilities as American-born individuals. Their finalized adoption makes internationally adopted individuals the legal children of their American and legal adoptive parents.

- No one adopted by a US citizen in a cross-country adoption should be denied US citizenship due to their date of adoption. Under the current segregated system (mirrored in most states by OBC access regulations) some adult adoptees enjoy full citizenship rights and responsibilities, while others are forced to either hide their status and live in fear or come forward, undergo cumbersome and unnecessary citizenship requirements and paperwork—and possibly set themselves up for investigation and under certain circumstances deportation to their country of origin—to enjoy those same rights and responsibilities.

- Adoptees were entitled to citizenship before their crimes or other miscues were committed. Commission or conviction of a crime does not supersede their adoption.

- International child adoption is not an immigration issue.

- US international adoptees had no say regarding their adoption and entry to the US. Their adoptions were facilitated by a network of adoption providers, professionals and US government agencies including the US State Department. They lack US citizenship through no fault of their own and should not be punished due to the negligence and lack of due diligence on the part of their adoptive parents, adoption professionals, or US immigration authorities.

- US international adoptees, should not be kept from grasping their citizenship rights due to fear of federal immigration retaliation if they come forward and attempt to apply for citizenship.

- The US, as a signatory to the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption, is obligated to extend all rights and privileges to its international adoptees.

- The deportation of adult adoptees controverts the belief that adoption is “forever,” and that adoptees are truly the children of those who adopt them. Deportation gives a black eye to US international adoption policy and sends a strong message to sending countries that adoption is temporary and subject to bureaucratic whim.

- For over 70 years US government policy has encouraged and facilitated cross-country adoption, yet without the protection of ACA, pre-2000 adoptees are disenfranchised from the country and adoption that embraced them.

Support

ACA 2019/20 is endorsed by a wide range of adoptee rights. Adoption reform, adoption advocacy, civic and religious organizations, and private businesses. (List from Adoptee Rights Campaign It will be amended with additional endorsers when appropriate).

- Adoptee Solidarity Korea – Los Angeles (ASK-LA)

- Adoptee Rights Law Center PLLC

- Adoption Links DC (ALDC)

- Adoption Support Services

- Advancing Justice (Atlanta, Chicago, DC, Los Angeles, San Francisco)

- Also Known As (AKA)

- Asian Adult Adoptees of Washington (AAAW)

- Asian American Bar Association of Houston\Asian Law Alliance

- Bastard Nation: the Adoptee Rights Organization

- Bethany Christian Services

- Boston Korean Adoptees (BKA)

- Chinese Adoptee Links (CAL)

- Chinese for Families

- City of Houston-City Council

- City of Houston- Mayor Sylvester Turner

- Concerned Citizens Coalition

- Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU), Shirley V. Hoogstra, President

- Council of Korean Americans (CKA)

- Donaldson Adoption Institute

- Evangelical Immigration Table

- 18 Million Rising

- Faith and Community Empowerment, Hyepin Im, President and CEO

- Ford Motor Company

- Friends of Korea

- GA Korean Grocers Association

- Harriet Tubman Center for Justice & Peace, Inc.

- Haydon Street Inn

- Holt International Children’s Services (HICS)

- Houston, Texas Mayor’s Advisory Council Member, Office of New Americans & Immigrant Communities

- Houston Chapter of Korean Sports Association, Texas

- Inter-Community Action Network

- Iowans for International Adoption

- Joynus Care

- Kokua Council of Senior Citizens of Hawaii

- Korean Adoptees of Chicago (KAtCH)

- Korean Adoptees of Hawaii

- Korean Adoptees of Houston, Texas

- Korean American Adoptee Adoptive Family Network (KAAN)

- Korean American Voters League, Houston, Texas

- Korean American Association of Chicago

- Korean American Association of Spokane Area

- Korean American Coalition of Oregon

- Korean American Coalition (National)

- Korean American Community Services

- Korean American Association of Houston, Texas

- Korean American Senior Citizen’s Association, Houston, Texas

- Korean Americans for Political Advancement (KAPA)

- Korean American Resource and Cultural Center (KRCC)

- Korean American Student Association, UIC (KASA)

- Korean-American Women’s Association of Atlanta

- Korean American Women’s Association of Houston, Texas

- Korean American Women in Need (KAN-WIN)

- Korean American Women’s Society

- Korean Churches for Community Development (KCCD)

- Korean Cultural Center of Iowa

- Korean Quarterly

- Korean Resource Center (KRC)

- Korean Society of Oregon

- Korean War Veteran

- Korean Women’s International Network

- Lost Sarees

- Magna Citizen Studio

- MinKwon Center for Community Action

- Mixed Roots Foundation

- National Asian Pacific American Bar Association (NAPABA)

- National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum (NAPAWF)

- National Association of Evangelicals (NAE), Leith Anderson, President

- National Center on Adoption and Permanency (NCAP)

- National Council For Adoption

- National Council of Asian Pacific Americans (NCAPA)

- National Foster Parent Association (NFPA)

- National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference (NHCLC), Samuel Rodriguez, President

- National Immigration Forum

- National Peace Corps Association (NPCA)

- New York Immigration Coalition (NYIC)

- North American Council on Adoptable Children (NACAC)

- We Are One America

- Oohjacquelina Handcrafted Jewelry

- Oregon Asian Pacific American Bar Association (OAPABA)

- Pacific Lutheran University

- Pearl S. Buck International

- Praise Clothing LA

- Presentation Sisters Associate

- Research Center for Korean Community at Queens College

- Siri Southwick-Young

- Sister Diaspora for Liberation

- Southern Baptist Convention-Russell Moore, President of Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission

- Truth and Reconciliation for the Adoption Community of Korea, (TRACK)

- Wesleyan Church

- University of Advancing Technology

- You Gotta Believe.org

- Washington Immigration Defense Group

- Wesleyan Church, Jo Anne Lyon, Global Ambassador

- World Hug Foundation, NY

- World Relief, Scott Arbeiter, President

Write! Call! Act!

-

Graphic: Adoptees for Justice Contact your Congressional Representatives and Senators in Washington and urge them to support and sponsor ACA amendments. ACA 2019-2020 runs out at the end of the year and if no action is taken, will need to be reintroduced.

-

Contact your local legislators and ask them to introduce and pass state resolutions in support of ACA and citizenship for all adoptees.

-

Urge organizations to which you belong to support adoptee citizenship

-

Follow social media pages that advocate adoptee citizenship; participate in actions such as petitions, tweet storms; subscribe and respond to action alerts.

Selected Resources

-

-

- US House of Representatives Directory

- US Senate Directory

- Sample State Resolution – Illinois

- Adoptee Rights Campaign

- Adoptee Rights Campaign – Facebook

- Adoptees for Justice

- Adoptees for Justice – Facebook

- Adoptee Rights Law Center

- ACT: Against Child Trafficking

- ACT: Against Child trafficking – Facebook

- Pound Pup Legacy Deportation Cases

-

Written by Marley Greiner with assistance from Shea Grimm

Please send corrections, additions, subtractions, updates to bastardnation3@gmail.com

Published July 1, 2016; Revised September 9, 2020

©2016, 2020 Bastard Nation: The Adoptee Rights Organization

_____________________

Bastard Nation: the Adoptee Rights Organization

PO Box 4607

New Windsor, New York 12553-7845

bastards.org 614-795-6819 @BastardsUnite

New York Adoptee Rights Coalition

New York Adoptee Rights Coalition